When we speak about the Vedas people usually tend to imagine only the Samhitā part of the Vedas. Samhitās are the Rig Veda, the Sāma Veda, the Yajurdev and the Atharva Ved. Samhitā in Sanskrit means ‘a collection’. So, the Vedas are a collection of the Suktas (hymns) or verses composed to worship Gods. We have often heard the names of the Samhitās, but may not have jumped deep into the ideas of ‘how Vedas look like?’, ‘what do they discuss?’, and many more.

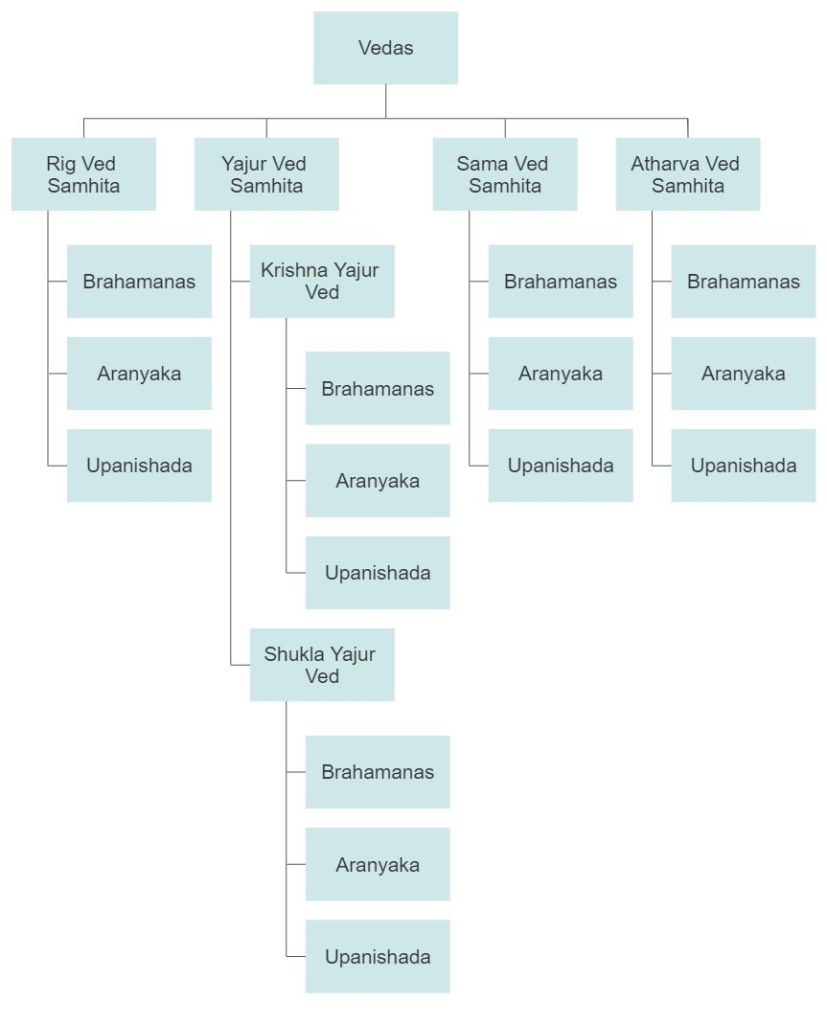

We saw in the Part-1 of the blog that Ved-Vyas organized the huge spread of the Vedas in the above mentioned Samhitās. However, with the term Vedas, apart from the Samhitās, also come the explanatory texts or scriptures of the Brahmanas, the Aranyakas and the Upanishads.

This general idea that the Vedas only mean the Samhitās has led many to think that the Vedas purely signify some abstract mantras and using of the mantras during Yajnas (oblation ceremonies).

To understand this, we first need to understand the conditions under which the Vedas were developed. The Rig Ved is the first of the Samhitās. One will never know when was the Rig Ved or the other Vedas revealed. However, when the Vedas were revealed to the great sages, and later transmitted, the population of the country was scarce. Let us be aware that we are discussing a time that is at least 5,000 years old if not more. Even though tribes were scattered almost all over India, much of the development has happened in the northern regions. Previously, it was thought that the Vedas came into existence in the regions of Punjab. However, if we get a little deeper into the Suktās, we will find that most of these verses were inspired by regions with large forests, several flowing rivers and heavy rains. However, Punjab didn’t see much rains and also much of the part of Punjab may not have had wide natural expanse. Thus, it is deduced that the original home of the Vedic Indians must be in a region named Brahmavarta which was later named as Kurukshetra falling between rivers Saraswati and Drishadvati, identified as today’s Chitang in the region of Ambālā. However, historians have not been able to trace the river Saraswati until today. Several attempts to identify with any existing river has failed.

The Rishis who developed the Vedic Suktās or hymns were not necessarily from the same or nearby regions. And also we have mentioned in part 1 of the blog that the entire traditional family of the Rishis was involved in developing the Suktās in a span of maybe several thousand years. This can be deduced from the fact that the Vedic Suktās have evolved from its original idea of limited terrestrial gods later leaning towards the universal idea of the gods in the later hymns of the Rig Ved and prominently in the later Vedas as well. We will see the evolution of the idea of gods from terrestrial to celestial and local to universal in another blog. The later addition of the scriptures of Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads also proves this point.

The Rishis who originally composed the Suktās of the Rig Ved were, Angiras, Kanva, Vasishtha, Vishvāmitra, Atri, Bhrgu, Kāshyap, Gritsamada, Agastya, and Bhārata. Later on, their traditional families including children and disciples evolved and added more Suktās. It is important to note that the Suktas were originally developed (or received) in their current form by the rishis not sitting in a common hermitage but at places which were sufficiently separated geographically. We can see this by the content of the Vedas. Rig Ved is a very good example of this process of compilation. The Suktās were written separately by the traditional families of these Rishis and also used in their everyday Yajnas. For a large time, these existed separately until Ved-Vyas compiled those Suktās and arranged them based on families who developed these.

The entire Rig Ved contains 10,552 mantras (also called as Rićās). The word Rig originates from Ric, which means the mantras. These 10,552 mantras are organized in 1,028 Suktās. Each Suktā roughly contain 10 mantras. The 1,028 Suktās are further organized into 10 mandalas (lit. circles). These mandalas are formed based on the Suktās composed by particular Rishi families. Thus, the 10,552 mantras are organized into 1,028 Suktās which in turn are organized into 10 mandalas. Each Suktā of roughly ~10 mantras of any one mandala (family) are dedicated to a particular deity (Example- Agni, Indra, Mitra etc.).

On linguistic studies and deeper analysis into the ideas presented in the Vedic compositions it is established that of the 10 mandalas, the mandalas 2-7 (6 nos.) are the oldest. Whereas, the mandalas 1 & 8-10 (total 4 nos.) seem to have been added in some other time.

The first Suktā of the first mandala that is dedicated to Agni and was revealed to ‘Madhuchchanda’ Vishvāmitra belonging to the family of the Vishvāmitra Rishi. Thus, it also shows that this Suktā was added later. The composer of the famous Gayatri mantra mentioned in the Rig Ved is Vishvāmitraen ‘Gathin’, another disciple of Vishvāmitra.

As Ved-Vyas compiled the Vedas, it became necessary that the written compilations were to be preserved for the future. Learning all the Vedas for one person was considered to be very difficult and also not viable. The Vedas could be lost again if were not preserved. This responsibility was handed over to a group of Rishis that were to preserve one Veda each. Thus, this gave rise in later ages to the concept of Vedic Shākhās (branches or recensions). The Rig Veda that we read today has come to us from one of the oldest Shākhās called as the Sākala Shākhā. In the late Vedic period the original Shākhās got divided into several Shākhās.

The Rig Ved and its associate scriptures were later developed and preserved by Śākala, Bāṣkala, Aśvalāyana, Śaṅkhāyana, and Māṇḍukāyana Shakhas. Of these only, the documents from Śākala and very few from Bāṣkala are left. Unfortunately, we have lost a large number of documents from the other Shākhās during the later invasions of India. In all 12 Shakhas are documented for Rig Ved. However, only five survive today.

Yajur Ved, for which 44 Shākhās were known, we find only six- Vajasaneyi Madhandina, Kanva; Taittiriya, Maitrayani, Caraka-Katha, Kapisthala-Katha existing today.

Sāma Veda was preserved in 8 Shākhās – āsurāyaṇīyā, vāsurāyaṇīyā, vātāntareyā, prāṃjalī, ṛugnyavaiagvainavidhā, prācīna yogyaśākhā, jñānayoga and rāṇāyaṇīyā.

Of the nine Shākhās of Atharva Veda- Paippalada, Tauda, Mauda, Shaunakiya, Jajala, Jalada, Brahmavada, Devadarsa and Chaarana-Vaidya, only one- Shaunaki Shākhās exists today.

The science of the difference in the Shākhās is called as Shakha-Bheda. The Vedic texts in different Shākhās primarily differ in the Varna (sounds) and Svara (accent). Even today if we listen to the Brahmans belonging to a particular Shākhās reciting the Suktas, we can discern the original Shākhā. So, next time you hear a Brahman reciting a Vedic mantra ask his Shākhā!

Still today we see that the most ancient Śākala tradition of the Rig Ved is followed in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala, Odisha, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh.

If we study the texts from the different Shākhās we will also see differences in the extended texts of Brahamana, Aryankaka and Upanishad for each Shākhā. The differences are seen more than the Samhitās since the later scriptures were added much later, but still in the Vedic age.

In the next part (part-3) of the blog, we will dive into the explanatory texts of Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads.

References-

- Kunhan R. (1958). Vedic Culture. Book: The cultural Heritage of India, Vol-1

- Keith AB (1922). Book: The Religion and Philosophy of the Vedas and Upanishads, Vol-1, Harvard Oriental Series Vol-31

One thought on “The story of the Vedas (Part 2- The Structure)”