The Vedas are all about the effect of sounds on the human system.

Until the end of the period when the books of the Brāhmanams were being completed, the Vedas were an oral tradition. Thus, these were referred to as the Shrutis. The Manusmriti states that Śrutistu vedo vigneyah (श्रुतिस्तु वेदो विज्ञेय) that means- know that Vedas are Shruti. The Shrutis consisted of the collection of all the Samhitas, Brāhmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads. Since the very beginning of the chanting of the Vedic mantras, the Rishis have laid much emphasis on the science of sound and its effect on human consciousness.

Until the end of the Brāhmanam period (when the books of the Brāhmanam were completed), there arose a need in the minds of the Vedic pundits to preserve this valuable treasure of knowledge from going extinct. Thus, the idea of a script to write down Sanskrit materialized. The sound system had to be organized to make it easily accessible and understandable to the students of the Vedas. Even though, the subject of sounds was well organized long before the written system came into practice, the age of the script has helped us to get deeper insights into the minds of the Vedic saints regarding the usage of the system of sounds.

This study of the system of sounds in the Vedas came to be later referred to as Shikshā and became one of the Vedangās (the body part of Vedas).

In the Brāhmanams it is mentioned that great harm is done to the meaning of the Shrutis if not pronounced correctly. Sanskrit not having a script in the early ages is partly because of the significance of recitation over sole contemplation of the meaning of these mantras. A lot of emphases must have been (and still today we can see) laid on the memorization of the Mantras with its proper accent, pitch, quality, length, etc.

Thus, it was necessary to lay down exact rules for the proper pronunciation of the mantras. The Vedangās are all written in unique sutra style. Sutras (lit. thread) are concise threads of principles laid down in short memorable forms. Since the Vedangās were to be transmitted orally there had to be a way for the students to memorize these subjects with ease. Thus, the sutras form a revolutionary style of Sanskrit literature, that could be easily handed down from one generation to the next. Before the Vedangās only small portions of the Brāhmanams and the Aranyakas were composed in the style of sutras.

Since the beginning, a lot of emphases was laid on the idea of the speech. The personified speech was called as Vać and was considered to be a revered deity. Even today a Hindu mind reveres the quality of speech and associates it with goddess Sarasvati.

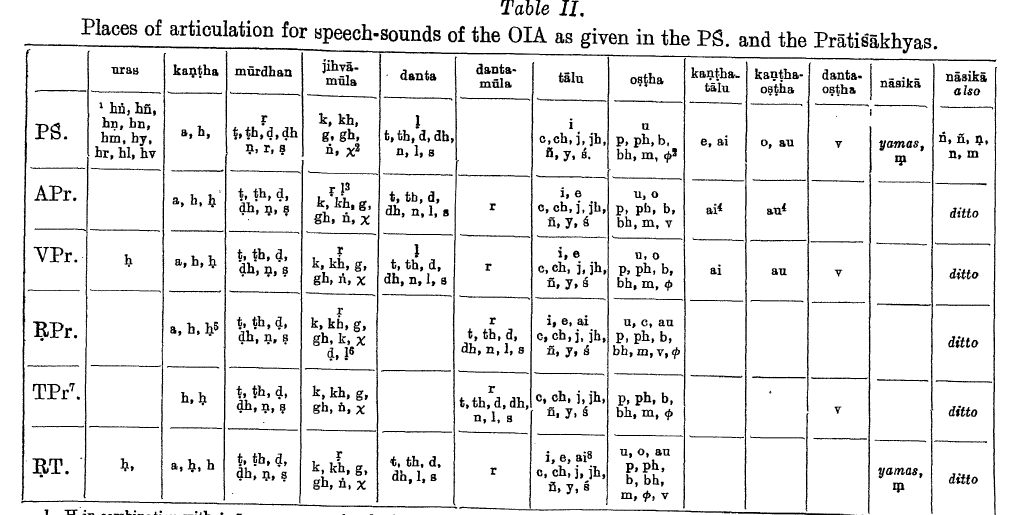

Meagre mentions of the subject of Shikshā can be found in the literature of Brāhmanams and Aranyakas. Researchers ascertain this to the fact that the written work of Shikshā gained much importance later in the times when the sub-recensions (branches of the branches of Vedic traditional schools) called as the Pratishākhyās. Thus, we find much of the written literature of the Shikshā texts in these Pratishākhyās. Thus, a Pratishākhyās are the manuals for the precise pronunciation of words. All that we know about the subject of Shikshā today comes from the preserved books on this subject by the Pratishākhyās. There are four such sub-recensions in which we find the books of Shikshā –

- Taittiriya Pratishākhyā

- Rk Pratishākhyā

- Vājaseneyi Pratishākhyā

- Atharvana Pratishākhyā

Of these, the Rk Pratishākhyā is the oldest but the Taittiriya Pratishākhyā is the most important. This is because the Taittiriya Pratishākhyā mentions the Shikshā works by the great scholar Pānini in its purest form.

The original, ancient and the first organized work on phonetics can be seen in the Maheshwari Sutras. It is said that Pānini was inspired by this work and later came up with his work on the science of sound systems in his great work of Pāniniya Shikshā. The Pāniniya Shikshā forms the turning point in the Indian idea of the science of phonetics. It is a small treatise which originally consisted of only 18 verses written in the Shloka form using Anushtubha Chhanda (meter of the mantras that restrict its length). The other great works like Mahābhārata, Rāmāyana etc. are written in Shloka form using the same meter. This small treatise of Pānini later underwent several changes by many to make it into a treatise as we find it today formed of a total of 60 verses. Pāniniya Shikshā forms the smallest treatise in Sanskrit literature.

The book of the Rk Tantra explains the lineage of transmission of the knowledge of sound. It says that the knowledge of Shiksha was first given by Brahma himself to Brihaspati, from Brihaspati it was transmitted to his disciple Indra, from Indra to Bhārdvāja, from Bhārdvāja to Vedic Rishis and finally to the Brāhmanas. The Pāniniya Shikshā is the most important source for understanding the subject of Shikshā. I will be quoting some very important rules of Pāniniya Shikshā that form the basis of Sanskrit phonetics today and are applied purely in the chanting of the Vedic mantras-

- On the significance of proper pronunciation:

- Uttering a mantra most properly leads one to attain the Brahma

- Sweetness, clarity of speech, the distinct pronunciation of words, correct accent, patience and ability to measure time in pronunciation are signs of right pronunciation

- On the contrary, shyness, shrill, indistinct articulation, excessive nasalization, excessively deep or uneven tone, mispronunciation, neglect to the place of origin of the sound, improper accent, harsh notes, an unnecessary gap of time between words, haste, wrong palatalization of words are the mistakes that a chanter must avoid.

- One must read quickly while memorizing the mantras, with average speed while using the mantras in ceremonies and very slowly while teaching to students.

- One must avoid a monotonous rising and falling of the intonation, must not recite too quickly, must not nod head while reciting, should not use a text during reciting, should have understood the meaning of the mantras and must not have a very low tone.

- On the origin of the sound:

- According to Pānini, the soul inspires the intellect and these together inspire the mind for a desire to speak. The mind further activates the fire element in the body. The fire drives the breath to enter and circulate inside the lungs. Later, the breath moves and circulates in the throat, from here it finally moves to the roof of the mouth. In this process, the breath generates different sounds based on the place where it circulates or reaches. For example- the circulation of breath in the lungs generates a soft (mandra) tone, that in the throat an intermediate tone (madhyama) and finally at the roof of the mouth produces a sharper (tāra) tone. Thus, the Vedic mantras must be chanted in mandra tone using the chest in the early morning, in madhyama tone during the midday and tāra tone during the evening based on the cycles of the Sun.

- The breath that moves upwards and is stopped by the roof of the mouth produces the speech sounds called varnas in Sanskrit.

- The sounds are classified based on the pitch, quantity, and place from where the sound is generated.

- Scientific organization of the sounds:

- Based on the pitch the sounds are classified as- 1) Udātta (high pitched), anudātta (low pitched) and svarita (medium in pitch). The musical notes later in classical Indian music have all evolved out these three basic pitches.

- Based on the place from where the sounds are generated (refer to the table for examples), these sounds are classified as-

- Chest (Uras): Ex. ह् (h)

- Throat (Kantha): Ex. अ (a), आ (ā)

- The base of the tongue (Jivhamula): Ex. क् (k), ख् (kh)

- With curled tongue or retroflex (Murdhan): Ex. ऋ (ṛ), लृ (ḷ)

- Teeth (Danta): Ex. त् (t), थ् (th), द् (d), ध् (dh)

- The base of the teeth (Danta-mula): Ex. र् (r)

- Tālu (roof of the oral cavity): Ex. इ (i), ई (ī), च् (ch), छ् (chh), ज् (j), झ् (jh)

- Oshtha (lips): Ex. प् (p), फ् (f), ब् (b), भ् (bh), म् (m)

- Kantha-tālu (staring with the throat and ending in the palatal area): Ex. ए (e), ऐ (ai)

- Kantha-oshtha (starting with the throat and ending in the lips): Ex. ओ (au), औ (au)

- Danta-oshtha (using both teeth and lips): Ex. व् (v)

- Nasal (Nāsika): Ex. ङ(nga), ञ(nja), ण(na), न(na)

- According to the origin, the sounds used in speech are either 63 or 64 (this uncertainty is mentioned in the Pāniniya Shikshā itself). Of these 21 are vowels, 25 types of sound endings (or stops), eight together formed of- semivowels, sibilants and varieties of h sound and four yamas – ङ(nga), ञ(nja), ण(na), and न(na).

- Based on the air or prāna that is used while generating the sound the vowels fall under either alpa-prāna [use less air, ex.- a (अ), ā (आ), etc.] and maha-prāhana [ex.- all variants of h (ह्) use a large amount of air].

- Based on the efforts (Prayatna) the sounds are again classified as-

- Sprishta– while generating these sounds, the tongue touches the places where the sound is produced. Ex. क् (k), ख् (kh), ग् (g), घ् (gh), ड्. (nga), च् (ch), छ् (chh), ज् (j), झ् (jh), ञ् (nja), ट् (ṭ), ठ् (ṭh) ड् (ḍ), ढ् (ḍh), ण् (ṇ), त् (t), थ् (th), द् (d), ध् (dh) न् (n), प् (p), फ् (f), ब् (b), भ् (bh), म् (m)

- Isha-Sprishta– while generating these sounds the tongue only slightly touches the places where the sound is produced. Ex. य् (y), र् (r), ल् (l), व् (v)

- Isha-dwi-vrita– Here the throat only partially opens while making the sounds. Ex. श् (ś), ष् (ṣ), स् (s), ह् (h)

- Vivrita: While pronouncing these sounds, the throat is completely open. Ex. अ (a), आ (ā), इ (i), ई (ī), उ (u), ऊ (ū), ऋ (ṛ), लृ (ḷ) ए (e), ओ (au), ऐ (ai), औ (au)

- Sanvrit: The throat is constricted while pronouncing. Ex. अ: (ah) as in विस्मय:

Thus, the sounds in Sanskrit are the most organized sounds of all languages. These sounds are said to be directly received from the soul or the Brahma. As they emerge out of the mouth they carry energy that can have an impact on the intellect and the mind. The subject of Shikshā has made immense contributions to the study of linguistics all over the world.

References:

- Book: Pāniniya Shikshā : Translations and commentary by Manmohan Ghosh

- V. Apte (1958). The Vedangas. Book: The Cultural Heritage of India. Vol-1

- Gautam K (2019). Phonetics and phonological rules in paniniya shiksha. ShriVaishnavi by Rastriyasanskrutam Sansthanam. Available at- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334670269

- Vyasa Shiksha